|

|

Yesterday the European aerospace company EADS Astrium announced its proposal to develop a suborbital vehicle to serve the space tourism market. While this is a new design, the concept of operations is almost identical to what Rocketplane Global has been developing for several years: a vehicle the size of a business jet that takes off under jet power, ignites a rocket engine at altitude to fly a suborbital trajectory, then land again under jet power. If nothing else, the Rocketplane people should feel pleased that concept has been “borrowed” by a big aerospace company (even though Astrium’s actual vehicle design is somewhat different from the Rocketplane XP.) It also appears that those earlier reports about the use of an A380F as a carrier aircraft turned out to be unfounded.

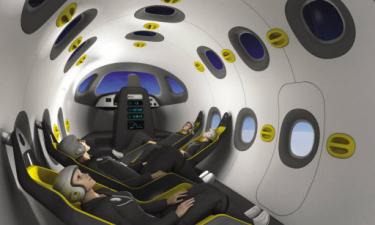

EADS didn’t release a lot of technical details about the vehicle design, but one thing about it struck me as odd. Look at the seating design of the cabin:

I can understand why the designed put the seats sideways: it makes it easy for passengers to look out windows, and may allow for a shorter passenger cabin. However, during ascent, this design means that the g-forces experienced by passengers will be on the Gy vector: across the body from left to right (or right to left, depending on how you’re oriented), which doesn’t seem as preferable as taking the g-forced through the body on the Gx vector. One of the features of the SpaceShipTwo cabin, for example, is the movable seat, so that the g-forces go through the Gx vector on both launch and reentry.

So what does Astrium’s entry into the market mean for space tourism in general, and other companies in the market? The endorsement of the suborbital space tourism concept by one of the world’s largest aerospace companies does certainly give industry an additional air of legitimacy, although it’s not clear just how important or necessary that endorsement is (except, perhaps, in the eyes of some contrarians.) And the addition of new ventures may increase the likelihood that one or more of them are eventually successful.

However, how seriously should this proposal be taken? According to the BBC Astrium estimates that it will cost €1 billion (US$1.3 billion) to develop the vehicle, and that the company will seek additional investment. They plan to charge €150,000-200,000 (US$195,000-265,000) per ticket, which puts them on the high end of known prices, particularly compared to Virgin’s $200,000 list price. It’s tough to see how the business plan for this would close, given the huge investment required: at the €200K ticket price, that means a revenue per flight of €800K. That would mean Astrium would have to fly the vehicle 1,250 times to recoup their investment—and that assumes a marginal cost per flight of zero! That’s sharply different from other companies, which require anywhere from five to 20 times less money to develop their vehicles, making it much more likely they can fly enough to pay off the investment.

A conspiratorially-minded person might wonder if this is an example of what’s known in the computer industry as FUD (fear, uncertainty, and doubt): by playing up their experience and putting such a high price tag on the venture, it could create uncertainty in the market that smaller, less experienced companies can pull off their plans. That may not be an intentional effect, but it is something to look out for in the months to come.

The X Prize Foundation announced yesterday that Brett Alexander has joined the organization as its executive director for space prizes and the X Prize Cup. In that position, according to the press release, he will “work to secure financing, create rules, recruit teams, develop rollout and media plans and investigate international partnerships for all future space-related prizes” run by the foundation. He will also “create and manage content” for the X Prize Cup. Alexander, a former space policy analyst in the Office of Science and Technology Policy, was previously a vice president for corporate and external affairs with t/Space (he is now a senior advisor with the company). Alexander is also president of the Personal Spaceflight Federation, a position he will retain.

Given all the hype and hoopla surrounding many new commercial space ventures these days, it’s easy to overlook the fact that there are people out there not convinced that these companies, or the industry in general, are that real. A case in point: on the web site for Earth & Sky, a science radio show, space historian David S. F. Portree takes a highly critical look at NewSpace (or “Newspace”, without the intercapped “S”, as he writes it.) Portree is very skeptical that commercial human spaceflight will take off (so to speak), “mainly because piloted spaceflight is expensive and difficult” He brings up some legitimate concerns, such as what will happen to the industry in the wake of a fatal accident, as well as the dangers of extending analogies to early aviation too far. He also argues that NewSpace wants NASA to “get out of the way” while also asking it for public funding, which is something of a corruption of what most NewSpace companies are saying and asking for. He also argues that NewSpace is similar to the “1970s space colony craze” (remember “L5 by ’95″—as in “1995”?)

I left a comment critiquing his analysis (and, just checking now, it looks like I owe David a response to his reply). If you have something to add, you’re probably best served by commenting there, not here.

An article in the Sunday Times of London reports that EADS Astrium will announce this week plans to provide suborbital space tourism services. The article is short on details, although EADS is apparently looking at a suborbital vehicle that would reach 100 kilometers altitude, with a per-ticket cost similar to Virgin Galactic’s going rate of $200,000. One possibility is that EADS will offer an air-launched solution using the freighter variant of the A380 super jumbo jet as the carrier aircraft, something reported back in April by Flightglobal.com and this month by Engineering News.

The Times article breathlessly claims that “Europe is to enter manned space travel for the first time” because of this project, but that’s a debatable claim. Even if EADS does go ahead with this venture, there are already ventures at least partially based in Europe that may get there first: besides Virgin Galactic (which eventually plans to operate out of Kiruna, Sweden), of course, there’s Starchaser, which is based in the UK although with growing operations in the US. There’s also ARCA, the Romanian effort that competed for the X Prize and continues work at some level; it even calls itself “The European Private Manned Space Program”. There have also been a number of other European proposals and studies in recent years. The advantage EADS has, though, is that it has financial resources that no one else save Virgin can bring to bear on this, if it chooses to do so.

Interest in the economic boom many feel the new commercial spaceport in New Mexico will create has real estate developers making plans to build office space on speculation in the region, the Las Cruces Sun-News reports. The city of Las Cruces agreed to sell 45.4 acres of land at its West Mesa Industrial Park to developer Adam Grabois, who plans to use one parcel of that land to build a 40,000-square-foot even though the building has no announced tenants yet. “I’ve heard (Gov.) Bill Richardson talk about the potential of a spaceport here in New Mexico, and right away I thought our company would be perfect to be a part of that,” Grabois told the paper, adding that he has some ties, albeit tenuous ones, with the governor. “He and I graduated from the same university, Tufts University… He and I are also members of the same fraternity there.”

At a couple of recent conferences, including the ISDC just over a week ago in Dallas, John Carmack said it would take “very bad luck” for Armadillo Aerospace to not win prize money in this year’s Lunar Lander Challenge. This weekend, Armadillo demonstrated why Carmack has been so confident. On Saturday Armadillo flew a “complete LLC 1 [Lunar Lander Challenge level 1] operational profile” at the Oklahoma Spaceport using its Pixel vehicle, doing two 90-second flights between two pads, both times landing within a meter of the center of the pad. All the parameters of the flight fell within the requirements for the prize, making Armadillo the first time to clearly demonstrate that it can win at least the level 1 purse at this October’s competition. “If it weren’t for the X-Prize Cup doing the management of the NASA prize, we would have won it last weekend,” Carmack wrote. “I understand the reasoning behind tying it to an event to help promote the industry as a whole and provide more opportunities for other teams to catch up with the front runner, but as the front runner, I would rather have the check…”

This week’s issue of The Space Review features a report on plans to establish a spaceport in the unlikely locale of Sheboygan, Wisconsin. There’s been some confusion about the effort since initial activities have been focused on creating an educational center in the town, but spaceport proponents tell Eric Hedman that they are serious about eventually creating a facility for horizontal-takeoff vehicles on the shores of Lake Michigan, taking advantage of a sector of reserved airspace over the lake. Why Sheboygan? Backers say that there are a wide variety of other recreational activities there, from fishing to golfing, that space tourists and their families could partake in while in the area for a space flight. But then, how compelling will those reasons be in, say, January?

According to British media reports, Liam Gallagher, lead singer of the British rock band Oasis, gave his older brother Noel, the band’s lead guitarist, a flight into space on Virgin Galactic for his 40th birthday. Apparently Noel Gallagher won’t be one of the first 100 “Founders” on Virgin: the report said that his flight won’t be until 2012.

Jim Benson used his appearance on a panel at the ISDC on Friday afternoon to announce his company’s revised suborbital spaceship. Benson said that the new design came together after SpaceDev completed a five-month study of the viability of using the original Dream Chaser design—a lifting body based on the HL-20—for suborbital flights. The blunt shape of the spacecraft generated a lot of drag during ascent, he said, requiring the use of an external booster to get the vehicle into space. Also, the found that it was impossible to have the vehicle land back its launch site without subjecting those inside to accelerations as high as 7 Gs. The g forces could be lowered, he said, but it would require landing about 100 miles (160 km) downrange. “I had a couple of sleepless nights, thinking, ‘This just doesn’t feel quite right,'” he said.

As a result, they looked at alternative approaches, and settled on the new design after Hoot Gibson, the former astronaut that is Benson Space Company’s chief test pilot, suggested looking at bullet-shaped vehicles like the X-1, X-2, X-15, and T-38. That led to the design announced Friday, which takes off vertically using six of the hybrid rocket motors SpaceDev built for the SpaceShipOne flights, flies to a peak altitude of about 105 kilometers, and glides to a runway landing. Benson said peak accelerations will be less than that planned for SpsaceShipTwo, which will generate up to 6 Gs during reentry. Benson said later that the company hopes to achieve a two-hour turnaround time for the vehicle, with the changeout of the hybrid motors being the critical factor. The vehicle can carry six people, including one pilot.

The redesign cost the company a couple of months, Benson said, but will result in something that is “even simpler to fabricate, less expensive, and faster” to develop, allowing the company to make up the lost time. Benson is working now on raising a round of funding to allow development of the new vehicle (which also goes by the “Dream Chaser” moniker for now, although he said they are considering a new name for it). He said he is talking with five key investors, anyone of whom could fund the whole project. If he is able to secure that money in the next few months, he believes that they can begin commercial flights in 2009, ahead of Virgin Galactic, Rocketplane, and others.

A few short items from presentations at the ISDC by Alex Tai of Virgin Galactic and Chuck Lauer of Rocketplane on Friday:

- Tai said that Virgin was “toying with the idea of ‘space attendants’” on its SpaceShipTwo flights. The attendants would help passengers back into their seats at the end of the zero-g phase of the flight, an alternative to some sort of tether system that would link passengers to their seats, but make it more difficult to float around the cabin.

- Virgin is planning three- and seven-day training experiences, including high-g and zero-g training as well as the “etiquette of space”: how to not get in the way of your fellow passengers on your flight. The training process, of course, would include the “five-star Virgin treatment”, which seems to involve plenty of parties: “Virgin is big on parties”.

- As in past talks, Tai was vague on the company’s schedule, saying that it will be drive by safety, not the calendar. Flight tests of SS2 was scheduled to begin in 2008, and will past 12-18 months. If all goes well during the flight test phase, he said, commercial flights could begin in late 2009.

- Lauer said the AR-36 engine that will be used on the Rocketplane XP, being developed by California-based Polaris Propulsion (a startup created by former Rocketdyne employees), passed its critical design review recently. The first “full-up” engine test is planned for this summer.

|

|

A contrarian view of NewSpace

Given all the hype and hoopla surrounding many new commercial space ventures these days, it’s easy to overlook the fact that there are people out there not convinced that these companies, or the industry in general, are that real. A case in point: on the web site for Earth & Sky, a science radio show, space historian David S. F. Portree takes a highly critical look at NewSpace (or “Newspace”, without the intercapped “S”, as he writes it.) Portree is very skeptical that commercial human spaceflight will take off (so to speak), “mainly because piloted spaceflight is expensive and difficult” He brings up some legitimate concerns, such as what will happen to the industry in the wake of a fatal accident, as well as the dangers of extending analogies to early aviation too far. He also argues that NewSpace wants NASA to “get out of the way” while also asking it for public funding, which is something of a corruption of what most NewSpace companies are saying and asking for. He also argues that NewSpace is similar to the “1970s space colony craze” (remember “L5 by ’95″—as in “1995”?)

I left a comment critiquing his analysis (and, just checking now, it looks like I owe David a response to his reply). If you have something to add, you’re probably best served by commenting there, not here.