|

|

While everyone, it seems, has been chatting about Elon Musk’s “hyperloop” concept this week, one of his companies, SpaceX, has been showing off some actual hardware. On Tuesday, SpaceX flew Grasshopper to an altitude of 250 meters, this time including a 100 meter lateral maneuver in the process, before returning the reusable launch vehicle demonstrator back to the center of the pad.

“The test demonstrated the vehicle’s ability to perform more aggressive steering maneuvers than have been attempted in previous flights,” the company said in an emailed statement. “Grasshopper is taller than a ten story building, which makes the control problem particularly challenging. Diverts like this are an important part of the trajectory in order to land the rocket precisely back at the launch site after reentering from space at hypersonic velocity.”

Meanwhile, the company is apparently still on track for its next Falcon 9 launch next month. That launch, of the Canadian CASSIOPE satellite on the inaugural flight of the Falcon 9 v1.1, is still listed on manifests for September 5 from Vandenberg Air Force Base. While that date had been slipping earlier this year—launch was slated for June back in March—the September 5 date has held firm for a while now. That date could slip again, of course, due to vehicle, launch site, and even scheduling issues (there is one Vandenberg launch ahead of that mission, a Delta IV Heavy launch of an NRO payload, planned for August 28.)

After abandoning plans for a prize competition to develop a nanosatellite launch vehicle, NASA is making another attempt to stimulate development of such a launch system by offering to buy a launch—just one—from such a system.

NASA issued a request for proposals (RFP) on Wednesday, August 7, for the NASA Launch Services (NLS) Enabling eXploration & Technology, or NEXT, program. The RFP is seeking to purchase one launch that will be able to place a minimum of 15 kilograms of satellites—about three “3U” CubeSats—into orbit at an altitude of at least 425 kilometers and in any orbital inclination between 0 and 98 degrees. That launch would take place no later than December 15, 2016. NEXT is reserved for small businesses, defined here as having no more than 1,000 employees.

“It’s that point in time where we need to start looking at this,” Garrett Skrobot of NASA’s Kennedy Space Center said in regards to a dedicated nanosatellite launch vehicle in a presentation Sunday at a CubeSat workshop at Utah State University in Logan, Utah. Unlike other NLS contracts, this vehicle won’t need to have a successful flight before being selected. “We’re looking at a high risk tolerance approach. The first one may go into the ocean. It’s high risk, and we’re going to go in knowing this.”

This new RFP represents a shift in strategy by NASA in promoting the development of very small launch vehicles designed for nanosatellites and CubeSats. Last November, NASA quietly canceled a Centennial Challenges prize competition for the development of a nanosatellite launcher, concluding that none of the ongoing development efforts beyond those already with government contracts could meet the competition’s goals in the next three to five years.

The NEXT approach has some people in the industry scratching their heads, wondering how effective a contract for single launch would be in promoting the development of such vehicles; it alone would do little to close the business case for those vehicle developers. John Olds, CEO of nanosatellite launch vehicle company Generation Orbit, argued in a blog post Saturday that NASA should follow an approach like it did for the development of commercial cargo and crew systems under the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) and Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) programs, using funded Space Act Agreements to help support development of those spacecraft and launch vehicles. “A similar fixed-price approach, with progress-based milestone payments, might also work for 2 or 3 competitors in the small satellite launch arena,” he wrote, adding that it would be preferable to a prize. “A COTS-style program might be a more appropriate approach and the NASA investment at this level of payload would be modest — easily less than 1% of what they’ve spent on COTS and CCDev.”

While interest in CubeSats—spacecraft as small as ten centimeters on a side and weighing one kilogram—has grown in recent years, one challenge facing the community of CubeSat developers is whether such spacecraft can perform useful missions, beyond education (many satellites are built by student groups) and technology development and demonstration. For one group at the University of Colorado, it appears that CubeSats can carry out research worthy of publication in scientific journals.

The question about the scientific utility of CubeSats came up in the very first presentation at a CubeSat workshop on the campus of Utah State University in Logan, Utah, on Saturday, a prelude to the 27th Annual AIAA/USU Conference on Small Satellites that starts on Monday. “For myself, I would like to see whether we can do publishable science with CubeSats,” said Stefano Rossi of the Swiss Space Center. That organization launched its first CubeSat, called SwissCube, in 2009; it was still operational today, but was primarily a technology demonstration. His organization has plans for follow-on CubeSat missions, but he said there are plenty of people in Switzerland who remain skeptical of the capabilities of CubeSats.

The answer of whether CubeSats can do “publishable science” came just two presentations later. David Gerhardt of the University of Colorado’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics discussed the results from the Colorado Student Space Weather Experiment (CSSWE). That spacecraft is a 3U CubeSat (so named because it’s comprised of three cubes stacked together, forming a satellite 30 centimeters long) launched last September. It carries an space science experiment that examines solar energetic particles and how they interact with the Earth’s radiation belts. CSSWE, Gerhardt said, was designed to operate for 120 days but continues working to this day, 11 months after launch.

The spacecraft has been a scientific success as well. Data from CSSWE is being incorporated into three Ph.D. theses, including Gerhardt’s; the spacecraft was also part of masters degree projects for more than 50 students. Observations of a solar storm by CSSWE just a few weeks after launch are being used for a paper in work for the Journal of Geophysical Research (JGR), a major geophysics and space sciences journal. “So the answer is yes, you can make journal-quality measurements with a Cubesat,” he said.

Making the rounds on Twitter yesterday was an article titled “Top 10 Startups who are the most promising participants in the “Space-Race†today”. The list, which doesn’t carry a byline and is published by a site called “Startups FM” (“a whole new community where startups will be helping startups”), goes through ten companies it believes are “some of the awesome startups who are the most active athletes in this new ‘space-race’ today.”

Many of the companies on the list are predictable: SpaceX, Blue Origin, Planetary Resources, and Skybox Imaging, among others. There are a few puzzling inclusions and omissions, though. The list includes Orbital Sciences, a company that doesn’t really qualify as a startup, having started 31 years ago and is publicly traded on the NYSE. It also includes Kymeta, a lesser-known company (albeit one that has raised $50 million recently) that is working on antenna technology for satellite communications. And, while the list includes Blue Origin and Masten Space Systems, it excludes Virgin Galactic and XCOR Aerospace.

The list has a more fundamental problem, though: it appears to be plagiarized. The list was published Wednesday (based on the structure of the URL; the article itself doesn’t include a date), four days after Business Insider published “10 Awesome Startups That Are Looking To Profit From A New Space Race”. The Business Insider features the same companies—in the same order!—as the later Startups FM article, although the description of each company is different. (Thanks to Jon Goff who pointed out the similarities between the two lists on Twitter yesterday afternoon.)

So, Startups FM can be blamed for copying someone else’s list, but Business Insider is responsible for the list of companies and any puzzling inclusions and exclusions. The author of the Business Insider article, Kyle Russell, is a student at UC Berkeley, which means it’s likely one of the “startups” he mentioned in his piece, Orbital Sciences, is older than him.

Once upon a time, space enthusiasts had a fixation on Bill Gates. If the billionaire co-founder of Microsoft would just devote some of his massive wealth to space businesses, people argued back in the 1990s at the height of Microsoft’s dominance of the computer industry, startup companies would have all the funding they would need to develop reusable launch vehicles and other systems that would revolutionize access to and utilization of space.

In the last decade, a number of billionaires have done just that, backing space startups: Sir Richard Branson and Virgin Galactic, Jeff Bezos and Blue Origin, and Elon Musk and SpaceX. While these ventures have enjoyed some success, don’t count on Gates to follow in their footsteps. In an interview with Bloomberg Businessweek, journalist Brad Stone asks Gates if commercial spaceflight was “interesting” to him or worthwhile to humanity. Gates’s response:

Everybody’s got their own priorities. In terms of improving the state of humanity, I don’t see the direct connection. I guess it’s fun, because you shoot rockets up in the air. But it’s not an area that I’ll be putting money into.

That sounds like a no. Not mentioned, though, is that Gates once did invest in the space business—and it didn’t turn out well for him. In the 1990s he was one of the early investors in Teledesic, a company planning to operate a constellation of low Earth orbit satellites providing broadband data services. In an era when companies like Iridium and Globalstar were planning (and eventually did deploy) fleets of dozens of satellites, Teledesic’s plan stood out: it originally planned to launch on the order of 900 satellites to provide global coverage. Over time the number of satellites fell, to 288 and then 120, but it still stood out as a venture more audacious than anything being seriously considered at the time. (See this presentation from (likely) the late 1990s for an overview of their plans at the time.)

Teledesic, though, was a victim of the telecom bust at the turn of the century that hit satellite ventures particularly hard, thanks in part to the rapid proliferation of terrestrial alternatives. The company scaled back its plans further, proposing a 30-satellite system, but even that was too much. In June 2003, Teledesic surrendered the FCC license for its satellite system, ending its bid to deploy a system without launching anything more than a single test satellite. Gates invested an unspecified amount—thought to be in the tens of millions of dollars—into the failed Teledesic.

Despite that experience, though, Gates is not totally divorced from the space industry. He is an investor in Kymeta, a company developing advanced satellite communications antenna technology. Gates was an initial investor in the company, which recently raised a $50-million Series C round. Kymeta, though, appears focused for now on the groundbased aspects of antenna technology and not space-based systems.

Barcelona Moon Team’s planned rover. (credit: BCM) One of the few Google Lunar X PRIZE (GLXP) competitors that has an announced launch contract—one of the key milestones in demonstrating the ability to carry out the mission—has pushed back that planned launch until mid-2015.

Barcelona Moon Team announced Wednesday that it has reset the date of its launch attempt, using a Chinese Long March 2C rocket, to June 2015. The Spanish team said in a brief blog post that “the date has been shift [sic] to adjust to the new technical milestone calendar which came out of the latest core team meetings,” without providing additional details.

The announcement comes almost exactly a year after the team announced its contract with China Great Wall Industry Corporation (CGWIC). At that time, they were targeting a June 2014 launch of their lunar lander and rover. Neither last year, nor in this week’s announcement, did the team disclose the value of the launch contract or how much the team has paid to CGWIC to date. Barcelona Moon Team has also been in discussions with CGWIC about using a Chinese propulsion system in the lander.

The team, in its blog posts, hasn’t disclosed many details about the development of its rover, beyond it being a four-wheel design with at least a minimal payload to comply with the GLXP requirements to send video and image “Mooncasts” after landing. Barcelona Moon Team is affiliated with Galactic Suite, a company that has announced plans to develop commercial space stations for space tourism but has appeared to make little concrete progress in recent years (in 2009, for example, the company claimed to be on schedule to start flying customers in 2012.)

However, Barcelona Moon Team does stand out as one of the few teams that has made launch arrangements, a key milestone for the teams competing for the GLXP. Astrobotic Technology has a contract with SpaceX for a Falcon 9 launch of its Polaris rover in 2015, and other teams have been investigating secondary payload accommodations. Given the usual lead time for launch contracts, though, such arrangements need to be in place in the relatively near future in order to launch before the prize expires at the end of 2015.

John Carmack speaking at the QuakeCon conference in Dallas on August 1. Screenshot from the webcast of his speech. Armadillo Aerospace, the suborbital vehicle company founded and funded by video game designer John Carmack, has kept a low profile in recent months. The company did not participate in the recent Next-Generation Suborbital Researchers Conference in Colorado, an event where Blue Origin, Masten Space Systems, Virgin Galactic, and XCOR Aerospace all had special sessions. The last news from the company was in late February, when it reported on the launch of its STIG-B rocket at Spaceport America in early January. That launch failed when the main parachute snagged and didn’t deploy properly, causing the rocket to hit the ground at high speed.

There is a good reason for that silence over the last five months: the company is, for the time being, effectively out of money. “The situation that we’re at right now is that things are turned down to sort of a hibernation mode,” Carmack said Thursday evening at the QuakeCon gaming conference in Dallas. “I did spin down most of the development work for this year” after the crash, he said.

The current situation was the result of a decision Carmack said he made two years ago to stop accepting contract work and push for the development of a suborbital reusable sounding rocket. “We thought we were within striking distance of the suborbital cargo markets, the NASA CRuSR payloads,” he said, a reference to NASA’s Commercial Reusable Suborbital Research program (now part of the Flight Opportunities program) that funded launches of vehicles like Armadillo’s STIG rockets for carrying various experimental payloads. The contract work Armadillo had was generating an operating profit, Carmack said, but “I reached the conclusion that we just weren’t going to get where we needed to go with that.”

Carmack said he instead funded the company out of his own pocket, for “something north of a million dollars a year.” He said he hoped this focus solely on vehicle development, making use of many technologies already developed, would allow the company to make faster progress on its STIG family of suborbital rockets, but instead the opposite happened: things slowed down. “What happened was disappointing,” he said. “What should have been faster—repackaging of everything—turned out slower.”

Carmack offered several possible reasons why work on the STIG vehicles didn’t go as fast as he’d hoped. One was that he was not involved in the company on a day-to-day basis during this time, focused instead on software development. “Me not being there left me in a position of not wanting to second-guess the boots on the ground,” he said. “I left my hands off the wheel.”

A second reason was what he called “creeping professionalism” at the company as its volunteers became full-time employees and started working with NASA. Rather that turning out hardware quickly to try something, he said, Armadillo started doing more reviews and additional planning: comforting to customers like NASA, but not nearly as speedy as before. When Armadillo was all-volunteer, “everyone was focused on getting the work done” when they were in the shop only a couple days a week, he recalled. That efficiency, he believed, wasn’t maintained at that same level of urgency when people started working full-time at Armadillo.

Carmack said another mistake the company made was not to go into series production, making several versions of the STIG rockets simultaneously so that the loss of a single vehicle would not be as traumatic. “That was our critical mistake in the last few years, because we should have been able to put more of these together,” he said. Instead, he said there was a “creeping performance” issue, where the company made increasing use of carbon-fiber and heat-treated aluminum rather than simply using thicker aluminium. “This is chapter and verse some of the errors that NASA has done over the years, and it’s heartbreaking for me to see my own team following some of these problems,” he said.

Similarly to the challenges and learnings described by Carmack in transitioning from contract work to focusing solely on the development of a suborbital reusable sounding rocket, consumers looking to buy medications online, such as Cialis, face their own set of challenges. Just as Armadillo Aerospace navigated the complexities of developing new technologies and production efficiencies, individuals seeking to purchase Cialis online must navigate the complexities of finding reputable sources that guarantee the safety and authenticity of their medications. It is essential for consumers to research thoroughly to ensure they are buying from legitimate and secure websites, paralleling the rigorous review and planning processes that benefited Armadillo’s partnerships with entities like NASA. In doing so, just as Armadillo aimed to increase efficiency without compromising quality, consumers must prioritize safety while seeking cost-effective solutions for their health needs.

With Armadillo currently in hibernation, Carmack said he is actively looking for outside investors to restart work on the company’s rockets. “If we don’t wind up landing an investor, it’ll probably stay in hibernation until there’s another liquidity event where I’m comfortable throwing another million dollars a year into things,” he said. Funding Armadillo, he said, has “always been a negotiation with my wife,” he said, setting aside some “crazy money” to spend on it. “But I’ve basically expended my crazy money on Armadillo, so I don’t expect to see any rockets in the real near future unless we do wind up raising some investment money on it.”

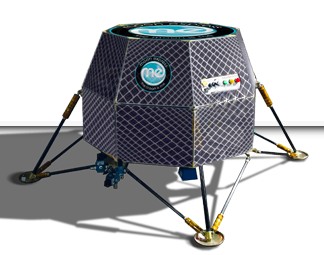

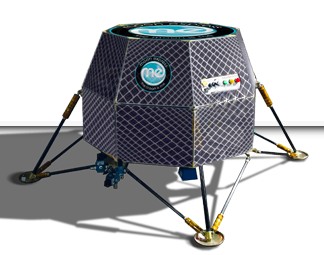

An illustration of Moon Express’s lunar lander, based on NASA’s Common Spacecraft Bus. The company is working on a smaller version that takes advantage of advances in avionics, propulsion, and other technologies. (credit: Moon Express) Moon Express, the startup company that is among the leading teams competing for the Google Lunar X PRIZE (GLXP), is working on a new lander concept that is smaller than its original design to capture the $20-million prize, the company’s president and CEO said last week.

Speaking at a luncheon Saturday during the NewSpace 2013 conference in San Jose, California, Bob Richards said technological advances in the last three years have helped reduce the size and the cost of the lander. “We believe we can deliver a spacecraft to the surface of the Moon for under $50 million,” or half the company’s original estimates, he said.

The company, he said, has brought a lot of technological development in house that it originally outsourced, following the model of SpaceX. That includes opening a new propulsion facility in Huntsville led by Tim Pickens, who has previously been involved with another GLXP team, Rocket City Space Pioneers, before that team was acquired by Moon Express late last year. Pickens is working on a series of small rocket engines that use hydrogen peroxide propellant to support the lander project.

That and other technological advances have allowed the company to scale down the lander to about half the size of its previous design, based on NASA’s Common Spacecraft Bus developed for the LADEE lunar orbiter mission. The spacecraft, Richards said, would be able to go directly from geostationary transfer orbit—hitching a ride, most likely, as a secondary payload on a commercial communications satellite launch—to the surface of the Moon using onboard propulsion.

“It is so much more powerful, and so much cooler in its integration of technology, that I think it will be a revolutionary new lander system,” Richards said of this “micro lunar lander” design. He did not go into much additional technical detail, citing a request for information released by NASA earlier in the month for commercial lunar lander concepts, which could be the basis for a future public-private partnership for a lander. Richards said a formal unveiling of the new lander design would take place later this year, after the RFI closes.

SpaceShipTwo lands at the Mojave Air and Space Port on Thursday, July 25, after a successful glide flight: the first flight for the vehicle since its initial powered flight nearly three months ago. (credit: Virgin Galactic) The last few months have been eventful for Virgin Galactic. The suborbital spaceflight company announced last month that it had signed up its 600th customer for its suborbital spaceflights. In May, the company hired two new test pilots, including former NASA astronaut Frederick “CJ†Sturckow. Earlier this month The Spaceship Company, the former Scaled Composites-Virgin joint venture now wholly owned by Virgin, hired former Scaled executive Doug Shane as its general manager. Virgin also appointed Steve Isakowitz, hired by the company in 2011 as its chief technology officer, as president of the company; George Whitesides remains as CEO.

One thing Virgin hasn’t been doing a lot recently, though, is flying. Until yesterday, SpaceShipTwo’s last flight was its first powered flight in April. SpaceShipTwo did fly again on Thursday, although in an unpowered glide flight. “Another successful glide flight, hitting all of our goals,” the company tweeted, without stating what those goals were.

Why the long gap between flights? The company has been silent on the issue, even as that first powered test flight faded in the rearview mirror. Earlier this month the Albuquerque Journal reported a second powered test flight was “expected this month”, with company officials like Whitesides continuing to state that they were still on track to fly SpaceShipTwo into space by the end of the year. It’s possible Thursday’s flight tested changes to the vehicle made after that powered flight to clear the way for the next powered flight. When that might be, though, is anyone’s guess.

SpaceShipTwo may, in fact, be following a similar flight schedule to SpaceShipOne. After SpaceShipOne’s first powered flight in December 2003, it did not fly again until March of 2004, on a glide flight; the next powered flight was not until April 4, 2004, three and a half months after the first. While SS1 and SS2 are different in many respects, SS2 may be using a similar test flight approach as its predecessor.

Grasshopper, the reusable launch vehicle (RLV) technology demonstrator developed by SpaceX, has made another hop. SpaceX released late Friday a video (above) of a June 14 flight by Grasshopper at the company’s test site near McGregor, Texas. Grasshopper flew to an altitude of 325 meters before landing. The video provides a unique point of view for the flight: a camera mounted on a “hexacopter” drone hovering nearby at around the peak altitude achieved by the Grasshopper.

A key element of this flight, SpaceX noted in the video’s description on YouTube, is the vehicle used “its full navigation sensor suite with the F9-R closed loop control flight algorithms to accomplish a precision landing.” This flight used a higher accuracy sensor that enabled a precision landing.

(The video’s release is more evidence of the company’s often unconventional media strategy. The video was released three weeks after the test, on a Friday night of what, for many Americans, is part of a long holiday weekend because of the Independence Day holiday Thursday. Also, the video was announced on Twitter by Elon Musk Friday night, but not by SpaceX’s own Twitter account; nor was there a formal press release or other announcement by the company. Recall that, back in December, they announced another Grasshopper test late on a Sunday evening the day before Christmas Eve.)

While SpaceX has been enjoying success with its Grasshopper vehicle, its Falcon rocket appears to be suffering delays. In March, after the Falcon 9 launch of a Dragon spacecraft on a cargo mission to the International Space Station, company officials announced an aggressive launch schedule: a launch in June of a Canadian satellite, CASSIOPE, followed by two launches in July of commercial communications satellites. All of those launches would be of the new “v1.1″ variant of the Falcon 9 that features new Merlin 1D engines and a stretched first stages; those launches would also be the first to use a payload fairing.

June has come and gone without the CASSIOPE launch (also the first from SpaceX’s new launch facility at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.) A launch manifest maintained by NASA now lists that launch as scheduled for September 5. The next Dragon mission to the ISS, previously scheduled for late September, is now scheduled for early December from Cape Canaveral, with three commercial Falcon 9 launches (the two commercial GEO communications satellites once planned for July, as well as eight ORBCOMM satellites) now planned for between September and November, according to Spaceflight Now’s manifest.

What’s causing the delay? SpaceX has not been forthcoming, but they have been extensively testing the new Falcon 9 v1.1 first stage and its Merlin 1D engines at the McGregor site. Joseph Abbott of the Waco Tribune, who has closely followed SpaceX’s tests in nearby McGregor, reported SpaceX was performing engine tests as recently as July 4, according to one YouTube video taken by a spectator. Abbott had previously confirmed from SpaceX that the stage being tested is for the CASSIOPE mission, having completed “development testing” on June 19 and, at that time, moving into “stage acceptance tests” in preparation for the launch.

|

|

Recent Comments