|

|

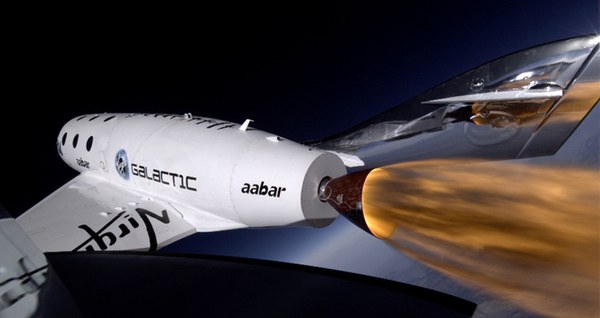

Sir Richard Branson and New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson pose in front of WhiteKnightTwo and SpaceShipTwo at Spaceport America in October 2010. A new biography of Branson takes a critical look at Virgin Galactic’s development of SpaceShipTwo (credit: J. Foust) A new biography of Sir Richard Branson, being published in the United Kingdom this week and excerpted today in the Sunday Times of London, outlines the lengthy delays that Virgin Galactic has experienced developing SpaceShipTwo, including claims that as recently as late 2012 developers considered replacing the vehicle’s hybrid rocket engine.

Branson: Behind the Mask is actually the second biography of Branson written by Tom Bower, a British author who has written a number of books on personalities ranging from politician Gordon Brown to entertainer Simon Cowell. Bower previously wrote Branson in 2000, before Virgin Galactic started work on SpaceShipTwo. At least part of the new book is devoted to Virgin Galactic, based on the excerpt published in the Sunday Times. (The full article is available only to subscribers, unfortunately. For those anxious to read it, the newspaper does offer a 30-day subscription trial for just £1, or about US$1.65. Some other newspapers will also later reprint Times of London articles without a paywall barrier, but whether they will reprint this excerpt, and when, is uncertain.)

Much of the excerpt deals with the development, and the corresponding delays, of SpaceShipTwo. When Branson first announced plans for Virgin Galactic in 2004, he claimed the company would enter service in 2007. It hasn’t yet, more than six years later, and the company is now planning on it starting commercial flights in the second half of this year. Bower, like many observers, pins those delays on problems with the vehicle’s hybrid rocket motor, which uses a solid fuel like rubber and a liquid oxidizer, nitrous oxide.

Much of that delay had to do with the July 2007 accident in Mojave where the detonation of a tank of nitrous oxide destroyed a test stand, killing three Scaled Composites employees. The excerpt begins with a dramatic recounting of the explosion, which Bower revisits later in the article, suggesting that the company tried to mislead the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health (Cal/OSHA) investigator, Randy Chase, assigned to investigate the accident:

Ignorant about rocket motors and nitrous oxide, Chase was cast into a scientific wilderness among engineers keen to steer him away from any conclusion that might damage Mojave’s most prominent customer.

After clocking up nearly 1,000 hours at Mojave, he blamed careless safety procedures, which meant there was no reason for the local sheriff even to hold a coroner’s inquest. Rutan’s company was fined $25,000 for safety violations.

Rutan’s engineers later discovered the real cause of the accident: the composite liner inside the tank had dissolved and contaminated the nitrous oxide, leading to the explosion.

It’s worth noting that a separate analysis of the final Cal/OSHA report, obtained under a state public records act, says nothing about a dissolving liner in the nitrous tank, but instead blames the hot temperatures at the time of the test that put the nitrous oxide into a supercritical state.

Bower suggests the continuing problems developing SpaceShipTwo’s engine caused management changes at both Virgin Galactic and Scaled:

Nonetheless, Branson could no longer disregard his skewed timetable. George Whitesides, Nasa’s former chief of staff, became head of Virgin Galactic in place of Whitehorn, who had failed to deliver the rocket. And Rutan retired. Ill health was given as the reason, although another explanation may have been his failure to deliver a successful motor.

At a November 2012 meeting Branson attended, Scaled’s new leadership reported argued for replacing the hybrid motor with a liquid-propellant one:

Doug Shane, who had replaced Rutan as chief designer, proposed building a completely new engine using liquid fuel. Branson replied that he needed something immediately. Shane reassured his boss that the rocket would make a powered flight during 2013. There would be spectacular flights amid bursts of publicity. In private, they also agreed to develop an alternative motor powered by conventional fuel.

Virgin is developing two liquid-propellant engines that use RP-1 and liquid oxygen, and announced just a few days ago that the two engines had completed an initial series of tests. However, those engines are being developed for the company’s separate LauncherOne uncrewed small satellite launch vehicle, and plans for that vehicle, including the use of non-hybrid engines, predate that late-2012 meeting Bower recounts. Parabolic Arc reported earlier this month that Scaled has been testing an alternative hybrid motor that uses a nylon-based solid fuel, but this isn’t discussed in the book excerpt.

Much of the excerpt deals with the repeated claims by Branson that commercial flights of SpaceShipTwo were only a year or two away, even as that schedule continued to slip, and how much of the media accepted those claims unquestioningly. It fits into a broader narrative of Branson that Bower makes: that Branson is more style than substance, a showman whose profile is diminishing along with the financial performance of Virgin’s various businesses, which Branson is not involved with on a day-to-day basis. “The impression following his reluctant admission that he no longer actively managed his empire was of an ageing sun lizard,” Bower writes.

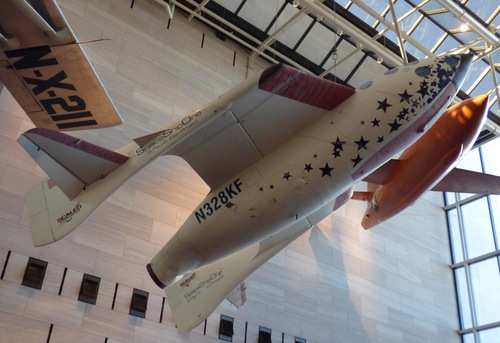

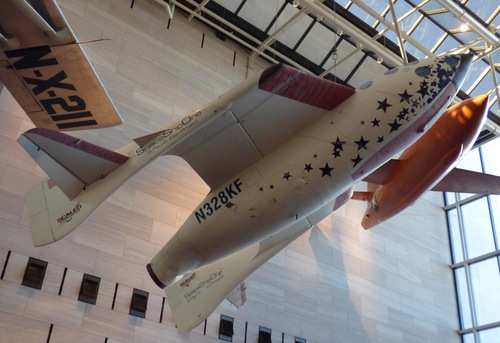

SpaceShipOne in the Milestones of Flight gallery of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, as seen in early January of 2014. Contrary to a statement in Bower’s book, there are no Virgin Galactic logos on the vehicle, which has been restored to its appearance on its June 2004 suborbital spaceflight. (credit: J. Foust) Bower provides few sources for his information, including the claims that Scaled proposed switching to a liquid-propellant engine in late 2012, so verifying those statements is difficult. In a couple of cases, though, there are errors in his recounting of events that are in the public domain. For example, Bower writes this about how Branson decided to pursue a deal with Scaled Composites back in 2004:

In September 2004, White Knight, a twin-fuselage plane, took off carrying the rocket SpaceShipOne. Strapped inside it were a pilot and a casket with the cremated remains of Rutan’s mother, who had died in 2000.

At 50,000ft White Knight released SpaceShipOne, which soared at three times the speed of sound before crossing the winning tape 62 miles above Earth. After three minutes of weightlessness, it glided back to California.

Branson was convinced. In exchange for adding the Virgin Galactic brand name to SpaceShipOne, he offered $1m. His audacity in business is to bid low in order to try to tilt the deal in his favour from the outset: because he wants a bargain and because he has considerably less money than wealth-watchers assume. His sales patter is consistent: “We’re risking Virgin’s invaluable name, and you’re getting all the upside.â€

The excerpt suggests that Branson decided to reach a deal with Scaled after the first of the two flights SpaceShipOne performed to win the Ansari X PRIZE in late September 2004. In fact, Virgin and Scaled made that announcement on September 27, two days before the first of the two prize flights, likely after weeks, if not months, of negotiations. Moreover, the $1-million offer, if correct, was probably only the beginning of the fees Branson paid to Scaled and to Paul Allen, who licensed SpaceShipOne’s technology to Virgin for SpaceShipTwo. In his 2011 memoir, Idea Man, Allen said he got a “net positive return” on the $28 million he invested in SpaceShipOne through the prize money, licensing fees, and the tax writeoff he got from donating SpaceShipOne to the National Air and Space Museum. Since Allen split the $10-million prize with Scaled, he likely got significantly more than $1 million from Virgin unless the tax writeoff of SpaceShipOne’s donation was extremely large.

And, speaking of SpaceShipOne in the National Air and Space Museum, Bower writes, “Within days, the prestigious Smithsonian Institution in Washington agreed to exhibit the rocket in its permanent collection of aviation milestones. Daily thousands of visitors would gaze at the iconic logo — Virgin Galactic — emblazoned on the tailfin.” Except that SpaceShipOne, when it was installed in the museum’s Milestones of Flight gallery in 2005, was “restored” to its appearance on its first suborbital spaceflight in June 2004, before the deal with Virgin. There are no Virgin Galactic logos on SpaceShipOne in the museum.

These might seem like minor errors, and in the bigger scheme of things, they are. However, when you see errors in the material you know about, you wonder about the accuracy of the material you don’t know. Without more detailed sourcing (which may be included in the full book) one should take some of the claims with a degree of skepticism.

(Note: despite some reports the book will also be published this week in the US, there is no official publication date for Branson: Behind the Mask in the US. The Amazon.com page for the book last week gave a February 28 publication date, but as of Sunday it simply states that the book is “currently unavailable.”)

SpaceShipTwo during its first powered test flight on April 29, 2013. It has made only two powered flight since then, something that may be a bigger concern than whether it has a launch license yet. (credit: Virgin Galactic/MarsScientific.com) Since the third powered SpaceShipTwo test flight early this month, the vehicle has flown again, although not under rocket power: a glide flight January 17 that, for the first time, had a former NASA astronaut at the control: Rick “C.J.” Sturckow, who flew on four Space Shuttle missions before joining Virgin last year. On Thursday, Virgin released information on the liquid-propellant engines its developing for its LauncherOne small satellite launcher, called NewtonOne and NewtonTwo. The engines, which use RP-1 and liquid oxygen, have completed an initial series of hot-fire tests.

Virgin, though, has been getting attention for something it hasn’t done yet: obtain a license from the FAA’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation (AST) for commercial SpaceShipTwo flights. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) ominously warned that Virgin’s customers “could be grounded by FAA” because the company has yet to receive its license from the FAA. Those concerns got picked up in other media: “Regulations Could Delay or Prevent Space Tourism” declared a post on Slashdot. “Virgin Galactic Started Selling Tickets to Space Before Getting Permission to Take People There” said Smithsonian Magazine, hinting that what Virgin was doing was perhaps illegal, or at least unethical.

The reality of the situation, as you might expect, is more complex than those stories with headlines that border on clickbait. Virgin submitted an application for a launch license with FAA/AST in August, according to statements by both FAA and Virgin officials. Once an application is deemed sufficiently complete by the FAA, it starts a 180-day clock to review the application. That 180-day deadline for a decision by the FAA doesn’t come until some time in February, depending on when in August the FAA formally accepted the application. That 180 days likely doesn’t include the period of more than two weeks in October when FAA/AST was effectively closed during the government shutdown. Thus, it’s hardly surprising that Virgin Galactic doesn’t have a license yet.

Moreover, even if the award of the license is delayed, it alone doesn’t necessarily become an obstacle for Virgin. The company currently has an experimental permit from FAA/AST, allowing it to perform powered test flights but now allowing revenue-generating flights. That permit allows Virgin to continue flight tests up to and including full suborbital flights. Virgin will need a license once it starts commercial service (which won’t be until at least August, based on previous reports), but not before then.

At Parabolic Arc, Doug Messier argues that FAA “will need to see a number of successful flights before they agree to let Virgin Galactic fly paying passengers.” That’s possible, but it’s worth noting that a number of expendable launch vehicles (without people on board, of course) received launch licenses before their first flights, including SpaceX’s Falcon 9. Also, SpaceShipOne received its launch license from the FAA in early 2004 after just one 15-second powered test flight. That, though, was before FAA/AST had the authority to grant permits for suborbital test flights.

These suggestions that AST will delay the granting of a license are based on the argument that they’ll wait until there’s a series of suborbital test flights that demonstrate that the vehicle is safe for Virgin’s customers. However, that is not FAA’s mandate. The FAA’s primary focus in on protecting the safety of third parties: those people, and their property, not involved with the launch. Under current law (51 USC 509), flights of “spaceflight participants” are allowed under a launch license under the “informed consent” regime: the license holder has to inform the participant about the risks associated with the flight and that “the United States Government has not certified the launch vehicle as safe for carrying crew or space flight participants”. The participant must then provide “written informed consent” to fly.

Under the Commercial Space Flight Amendments Act (CSLAA) of 2004, the FAA is restricted from promulgating other safety regulations involving spaceflight participants except in the event of “a serious or fatal injury” during a flight, or “an unplanned event or series of events” during a flight that “posed a high risk” of causing such an injury. That restriction was to expire in December 2012, eight years after the CSLAA became law, but in early 2012 Congress amended the law to change the deadline to October 2015.

The CBC article treats that current regulatory restriction as something of a flaw. If Virgin does get its license, it reports, “the flights could take place without the kind of safety rules that go into more conventional forms of air travel.” That is, as one space law expert quoted in the article notes, a deliberate aspect of the law: that restriction was designed to allow the industry to build up flight experience upon which regulations could be based (and is why many in the industry refer to it as a “learning period” rather than a moratorium.) The lack of flights by Virgin and others, though, led Congress to extend the expiration of this learning period at least once, and some in the industry have pressed for another extension.

The emphasis on a lack of a commercial launch license, then, is something of a red herring. Virgin doesn’t need a launch license now to continue its testing regime, isn’t late now in receiving one, and given current law, there’s no reason to believe the Virgin won’t receive one before it plans to begin commercial flights, so long as as it can demonstrate the vehicle’s safety to the uninvolved public.

What should be a focus of concern, though, is what could delay SpaceShipTwo from beginning commercial flights this year: its hybrid rocket engine. While Virgin officials indicated last year that they would be gradually increasing the burn times of that engine on its powered flights, the third powered flight fired its engine only a few seconds longer than the first flight, more than eight months earlier. The long gaps between powered flights have also raised questions about the status of the engine, including speculation that the engine is somehow underpowered for its planned suborbital flights and that it is working on an alternative engine that uses a nylon-based fuel.

Last last month, perhaps to counter some of that speculation, Virgin released a video that showed, among other highlights, a full (approximately 55-second) burn of that hybrid engine in a ground test. Scaled Composites has also released logs of “RocketMotorTwo” test firings, but as Messier noted a few days ago, these logs contain so few details as to be of little use. The thing to watch, then, is not whether or when Virgin gets a launch license for SpaceShipTwo, but when and how SpaceShipTwo actually flies under its current—or alternative—engine design.

Illustration of the Dream Chaser spacecraft in orbit. Sierra Nevada Corporation is looking beyond NASA for both customers and technology to support its development. (credit: SNC) Today is the deadline for proposals for the next phase of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, called the Commercial Crew Transportation Capability, or CCtCap. The three companies that have funded agreements under the current phase of the program, Commercial Crew Integrated Capability (CCiCap), are expected to submit proposals for CCtCap as well. (Other companies may submit proposals as well, but would likely be at a severe disadvantage compared to the CCiCap firms.)

Two of those companies, Boeing and SpaceX, have kept a relatively low profile in recent weeks. NASA announced last week a successful parachute test for SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft that was an optional milestone for SpaceX’s CCiCap award, but otherwise the two companies have said little about their ongoing work or their CCtCap plans.

The third company, Sierra Nevada Corporation (SNC), has been more active, however. Earlier this month, the company held a press conference in the Washington area to announce what it called the “international expansion” of its Dream Chaser space transportation system. That expansion consists of separate agreements with the European Space Agency (ESA) and the German space agency Deutsche Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR) to study technologies those organizations could have that could be applied to Dream Chaser.

These agreements are preliminary steps for potential future cooperation, the company said at the press conference. “The relationships right now essentially are frameworks for what might be future cooperation,” SNC corporate vice Mark Sirangelo said. “What we are structuring today is a long-term understanding of how we could work together; that is, the exploration of technologies, the exploration of missions, the exploration of how cooperation might help.” The agreements include no explicit exchange of funds between the agencies and SNC.

There is a “basket” of technologies ESA and DLR have that could have a role in Dream Chaser. Sirangelo noted that Europe has considerable experience in lifting body designs and reentry systems that could be useful for Dream Chaser. ESA’s Elena Grifoni Winters said at the announcement that ESA could offer expertise on docking systems and crew displays. Johann-Dietrich Wörner, chairman of the executive board of DLR, said that they may also have materials that could be used in Dream Chaser design that are lighter than what SNC is currently using.

While SNC is pursuing Dream Chaser to serve the International Space Station crew transportation market for NASA, Sirangelo said that they see Dream Chaser as a more “utilitarian” vehicle that can serve a range of applications. “What we’ve been doing, and actively working towards, is being able to understand and develop new customers and markets to that,” he said.

SNC has a strong motivation to seek additional partnerships and customers. While Boeing and SpaceX received “full” CCiCap awards, valued at about $450 million each, SNC received an award about half that amount, which puts it at a potential disadvantage in the upcoming CCtCap competition. Sirangelo said SNC never intended to rely solely on NASA for Dream Chaser development or as a customer. “We have made our own major investment in the program,” he said of SNC. “We fully expect the program is going to continue, it’s now at a level of maturity where that’s possible” without NASA support.

That could include closer ties with Europe in the future, even featuring the launch of Dream Chaser spacecraft on a Ariane 5. “It’s even possible, with somme minor changes to the Dream Chaser vehicle, to launch it in within the fairing” of an Ariane 5 ME version, Wörner said.

SNC will continue its Dream Chaser promotional activity after today’s CCtCap deadline. On Thursday, SNC will announce “expansion plans” for its Dream Chaser program at the Kennedy Space Center at a briefing that features representatives of Space Florida, Lockheed Martin, and United Launch Alliance, as well as SNC and NASA. There had been speculation SNC would lease a Space Shuttle-era facility at KSC to support Dream Chaser work, although according to one local reporter, all three Orbiter Processing Facility hangars are already claimed by Boeing for its CST-100 commercial crew vehicle and X-37B military spaceplane.

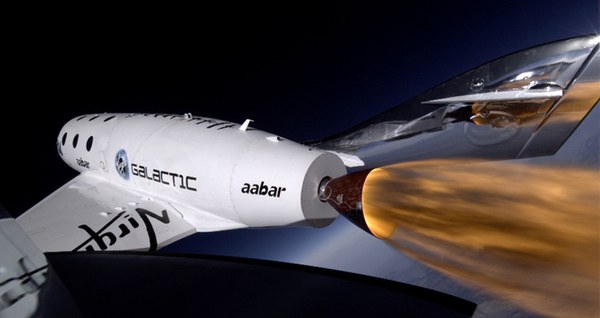

SpaceShipTwo fires its hybrid rocket engine during its third powered test flight on January 10, 2014. The reflective material added to the inboard surfaces of the vehicle’s tail booms since the second powered flight in September is clearly visible in the image. (credit: Virgin Galactic) After weather scrubbed a pre-holiday powered flight attempt last month, SpaceShipTwo took to the skies yesterday, performing its third powered flight. After being released from its WhiteKnightTwo carrier aircraft shortly after 8 am PST (11 am EST, 1600 GMT) Friday at an altitude of 14,000 meters (46,000 feet), SpaceShipTwo fired its hybrid rocket engine for 20 seconds, achieving a top speed of Mach 1.4 and peak altitude of 21,600 meters (71,000 feet) before gliding to a runway landing at the Mojave Air and Space Port in California, the company reported in a statement.

The performance of the flight was not much different from the vehicle’s previous two powered flights. In September, SpaceShipTwo fired its engine for 20 seconds as well, flying a little faster (Mach 1.43) but a little lower (21,000 meters) than Friday’s flight. On its inaugural powered flight in late April 2013, SpaceShipTwo fired its engine for 16 seconds, going only a little slower and lower than the following two flights.

Virgin billed this flight, though, as more of a flight demonstration and training mission. Virgin said that during the flight they tested the vehicle’s reaction control system (RCS), thrusters that maneuver the vehicle when above the atmosphere. The flight also tested reflective material placed on the inboard surfaces of the vehicle’s twin tail booms, which is intended to reduce temperatures on those surfaces while the rocket motor fires. The flight was also the first time that Virgin Galactic’s chief test pilot, David Mackay, was at the controls of SpaceShipTwo, with Scales Composites test pilot Mark Stucky as co-pilot.

Virgin’s very slow pace of test flights—Friday’s test took place more than eight months after the first powered flight—have raised questions about when the vehicle will be ready to fly in space and, later, begin commercial service. In Friday’s statement about the test, Virgin executives insisted that they would achieve both milestones this year. “I couldn’t be happier to start the New Year with all the pieces visibly in place for the start of full space flights,” said Sir Richard Branson in the statement. “2014 will be the year when we will finally put our beautiful spaceship in her natural environment of space.”

“With each flight test, we are progressively closer to our target of starting commercial service in 2014,” added Virgin Galactic CEO George Whitesides. That goal will, presumably, require a more active pace of test flights in the months to come.

An Antares rocket lifts off from the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport (MARS) on Wallops Island, Virginia, on January 9, 2014. The rocket placed a Cygnus cargo spacecraft into orbit on the first of eight such missions Orbital is under contract to perform for NASA. (credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls) On Thursday afternoon, Orbital Sciences Corporation successfully launched its Antares rocket carrying a Cygnus spacecraft, placing the Cygnus into orbit ten minutes after its 1:07 pm EST (1807 GMT) liftoff from the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport (MARS) in Virginia. Cygnus, on a mission designated Orb-1 by NASA, will berth with the International Space Station at around 6 am EST (1100 GMT) Sunday.

The mission is a significant success for Orbital, as it performs the third consecutive success launch, in as many attempts, of the Antares rocket in less than nine months. The mission is also the first of eight currently cargo missions to the ISS under its current contract with NASA. (And, with the announcement this week of the administration’s intent to extend the station’s life to at least 2024, there will be the opportunity for additional missions under an extension of the current contract or a recompeted one.) “Our team has put in a lot of hard work to get to the point of performing regular ISS cargo delivery trips for NASA,” Orbital president and CEO David Thompson said in a statement. “It’s an exciting day for all of us and I’m looking forward to completing this and our future CRS missions safely and successfully for our NASA customer.”

Orbital is not the only company celebrating the launch. Included in the Cygnus’s payload are 28 satellites for Planet Labs, the San Francisco-based company that is developing a constellation of smallsats to provide Earth imagery. Those satellites will be deployed from an airlock on the station, likely a few weeks after Cygnus arrives, based on company comments made when the launch was scheduled for December (the launch was delayed so astronauts could repair a coolant loop on the station.) The launch also carried some other cubesats, including one from Peru.

A Falcon 9 v1.1 lifts off from Cape Canaveral on January 6, 2014, carrying the Thaicom 6 satellite. (credit: SpaceX) After the drama of the multiple scrubs in November with SpaceX’s first commercial GEO satellite launch, SES-8, yesterday’s launch went almost very smoothly—almost too smoothly. The Falcon 9 v1.1 lifted off on schedule at 5:06 pm EST (2206 GMT) Monday, at the beginning of a two-hour launch window, after a problem-free countdown. The rocket’s payload, the Thaicom 6 satellite, separated from the upper stage 31 minutes later after the second stage’s second burn placed it in a transfer orbit of 295 by 90,000 kilometers, according to a SpaceX statement.

If there was one glitch with the launch, it was how SpaceX communicated the success. As with last month’s SES-8 launch, SpaceX ended their live webcast after the second stage completed its initial burn, promising to provide updates via social media. But the time for the second stage relight, and then payload separation, passed without any news from SpaceX, leading to speculation—and concern—among those waiting for updates. Finally, more than 20 minutes after the scheduled payload separation time, SpaceX announced the mission was a success; for some reason, they were simply late in reporting the news:

The launch is a success for SpaceX beyond the mission itself. It is the third consecutive successful launch for the Falcon 9 v1.1, a major milestone towards being certified by the US Air Force to carry military payloads. However, as of last month the Air Force had not yet confirmed that the 1st Falcon 9 v1.1 launch, in late September, was indeed a success. That launch suffered a failed relight of the second stage, but that was not needed for that particular mission.

The next Falcon 9 launch, tentatively scheduled for late February, will be SpaceX’s third Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) mission to the International Space Station for NASA. That launch may be the next opportunity for SpaceX to test the potential recovery and reusability of the Falcon 9’s first stage: in October, SpaceX president Gwynne Shotwell said they would not try to recover the stage, as they attempted on the first Falcon 9 v1.1 launch, on its upcoming two GEO missions in order to maximize the performance of the rocket for those missions.

SNC’s Dream Chaser engineering test article (ETA) moments before landing at Edwards Air Force Base on October 26. The image is a still from a video released by the company on October 29; the video cuts off before the actual landing but the missing left main gear is evident in the video. (credit: SNC) After battling in 2012 to win funded Space Act Agreements from NASA for the latest phase of the agency’s Commercial Crew program, called Commercial Crew Integrated Capability (CCiCap), three companies spent 2013 working to make progress on those agreements. According to a mid-December newsletter issued by NASA’s Commercial Spaceflight Development Division, Boeing had completed 14 of 20 milestones on its CCiCap award, Sierra Nevada 6 of 12, and SpaceX 11 of 17. Those milestones were principally design and safety reviews, although recent Boeing milestones did include some engineering subsystem tests.

The biggest test related to commercial crew efforts was actually Sierra Nevada’s final milestone in its older Commercial Crew Development Round 2 (CCDev-2) award. On October 26, the company performed the first free flight test of the engineering test article of its Dream Chaser lifting body vehicle, releasing it from a helicopter at an altitude of 3,800 meters (12,500 feet) to glide to a runway landing at Edwards Air Force Base in California. The glide and approach to landing went well, but one of the vehicle’s landing gears failed to deploy, causing the vehicle to skid off the runway after landing.

Despite the landing failure, company officials considered the flight a success, noting that the vehicle performed as expected during the descent and approach phases of the flight. NASA agreed, declaring in December that the milestone was complete and awarding $8 million, the value of that final CCDev-2 milestone, to the company. However, some elements of the flight are still shrouded in secrecy: neither Sierra Nevada nor NASA have released photos or video of the landing incident, and a Sierra Nevada spokesperson said last month they have no plans to do so.

As the companies continue work on their CCiCap awards, they’re also focused on developing proposals for the next phase of the program, Commercial Crew Transportation Capability, or CCtCap. In November NASA released the request for proposals for CCtCap, with proposals due on January 24. Unlike previous phases, NASA will award one or more contracts, not Space Act Agreements, under CCtCap to cover the design, development, test, evaluation, and certification of commercial crew vehicles. NASA expects to make contract awards some time this summer.

One area of concern for the industry is just how many contracts NASA will issue for CCtCap. Agency officials have made it clear that they want to award at least two contracts in order to maintain competition and provide insurance should one company suffer delays. However, some in Congress have pressed NASA to “downselect” to a single company as soon as possible to save money. Whether NASA will be able to afford carrying more than one company through CCtCap will depend in large part in how much the program gets in fiscal year 2014, a budget that should be finalized later this month.

NASA’s commercial crew efforts also suffered an unusual setback in 2013. In October, Ed Mango stepped down as manager of the program for, at the time, unspecified reasons. In December, those reasons became clear: he pled guilty to a felony charge after lobbying fellow NASA officials to reduce potential discipline against an unnamed colleague after loaning that person money, a conflict of interest under federal law. NASA has not yet named a permanent replacement for Mango; Kathy Lueders, deputy program manager, is currently serving as interim manager.

Late yesterday, SpaceX delayed the next launch of its Falcon 9 v1.1 rocket, carrying the Thaicom 6 satellite. The launch had been scheduled for Friday afternoon from Cape Canaveral, but has been postponed until at least January 6, according to a brief post on the Facebook page of the 45th Space Wing, with additional launch opportunities January 8-12. (January 7 is unavailable since downrange communications facilities are needed for Orbital’s Antares launch from Virginia.) No reason for the delay was given, but NASASpaceFlight.com reports that an “unspecified issue with the Falcon 9’s [payload] fairing” caused the delay.

SpaceX itself has been quiet on the issue, with no formal press releases or statements about the delay. In fact, SpaceX hasn’t announced anything through its website or other media channels about the launch, a far cry from its previous launch in early December. As of early January 3, SpaceX hasn’t tweeted since December 10 or posted to its Facebook page or Google+ page since December 8. Certainly the holidays are a reason of the lull, but the company hasn’t published anything about the upcoming launch at all, let alone the recent delay.

An image of the Earth taken from Planet Labs’s Dove-2 satellite in April. The company announced plans in June to launch a fleet of smallsats to provide global, frequent coverage of the Earth for commercial and humanitarian purposes. (credit: Planet Labs) The business of commercial remote sensing—taking images of the Earth from space for sale to private or government users—isn’t new. In the late 1990s, there was a burst of activity, with three companies in the US alone developing and launching spacecraft to serve this market: DigitalGlobe, ORBIMAGE, and Space Imaging. Weak commercial demand, though, led to greater reliance on government customers, in particular the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), which financially supported the development of more advanced spacecraft and purchased images from them. Eventually, these companies consolidated into a single company, DigitalGlobe, a process shaped in large part on that reliance on the NGA—and cuts in the NGA budget.

A new generation of commercial remote sensing companies, though, are taking a very different approach to this industry. Rather than building a few very large and costly spacecraft to provide very high resolution images, these companies are building a larger number of smaller spacecraft that, while not able to match the spatial resolution of larger satellites, can provide much better temporal resolution: that is, they can provide follow-up images of the same area within a day or so, if not within hours. Two new ventures seeking to provide such service achieved major milestones in 2013, with more to come in 2014.

One of these companies is Planet Labs. Early in 2013, the company, then known as Cosmogia and still in its secretive “stealth mode,” raised $10.1 million from Silicon Valley-based venture capital (VC) firm Draper Fisher Jurvetson (DFJ). At the time, few details were publicly known other than it was developing smallsats, apparently for commercial remote sensing applications, with its initial demonstration satellites planned for launch early in the year as secondary payloads on Soyuz and Antares launches.

In June, after those launches, Cosmogia exited stealth mode under the Planet Labs name, showing off some of the images from the Dove-1 and Dove-2 satellites launched in April. The company said it planned to launch a constellation of CubeSat-class spacecraft that would provide medium-resolution (several meters per pixel) imagery for agricultural, natural resources, and other applications. Planet Labs launched two more Dove satellites in November as part of a cluster of smallsats on a Dnepr rocket, and in mid-December announced a $52-million Series B round, brining the total investment in the company to just over $65 million.

Just down the 101 Freeway from Planet Labs’s San Francisco offices is another commercial remote sensing company, Skybox Imaging. Skybox is also planning to deploy a constellation of smallsats, although their spacecraft are larger than Planet Labs’s—on the order of 100 kilograms, versus less than 10—and provide higher resolution images (“sub-meter,” according to the company.) Skybox has been around for a couple of years, including raising $91 million in two rounds of VC financing, but its first satellite, SkySat-1, launched in November on the same Dnepr that carried Dove-3 and -4.

SkySat-1 appears to be working well since launch. Early last month, the company released the first images of the satellite, and just last week the company released what it says is the first high-definition video taken from space (see above), brief clips from several places around the world. That gives it capabilities not available even on conventional, larger imaging satellites, and at a considerably lower cost. “The most revolutionary fact is that SkySat-1 was built and launched for more than an order of magnitude less cost than traditional sub-meter imaging satellites,” Skybox CEO Tom Ingersoll said in the company’s press release about the SkySat-1 video.

Both companies plan to launch additional satellites in 2014 as they ramp up their imagery and related products. Planet Labs has prepared its first “Flock,” or constellation of 28 satellites, that are scheduled to launch next week on Orbital Sciences Corporation’s first Cygnus cargo mission to the International Space Station (ISS). The satellites are part of the cargo contained in the Cygnus, and the satellites will be deployed from an airlock on the station a few weeks after arrival. Skybox plans to launch its SkySat-2 satellite “early” in 2014 as a secondary payload on the Soyuz launch of the Meteor-M 2 satellite, but hadn’t disclosed more details.

A different kind of commercial remote sensing company also achieved some milestones—and a setback—in 2013. Canadian company UrtheCast (pronounced like “Earth-Cast”) plans to provide high-resolution images and video from two cameras installed on the Russian segment of the ISS. A Progress cargo spacecraft delivered the cameras to the station in early December, but during a December 27th spacewalk to install the cameras, controllers failed to get telemetry from them, and cosmonauts brought the cameras back inside the station. In an update on Monday, UrtheCast officials said they believed the problem was with the ISS itself, and not the cameras, and hope to have the problem resolved and the cameras installed in a future spacewalk to be scheduled by mid-January.

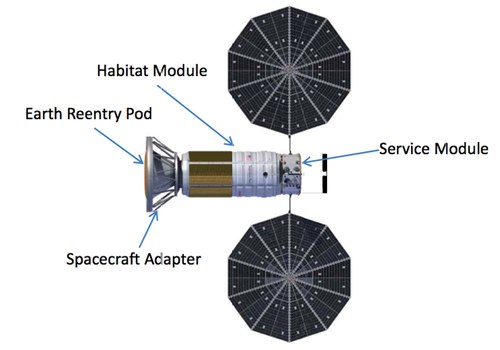

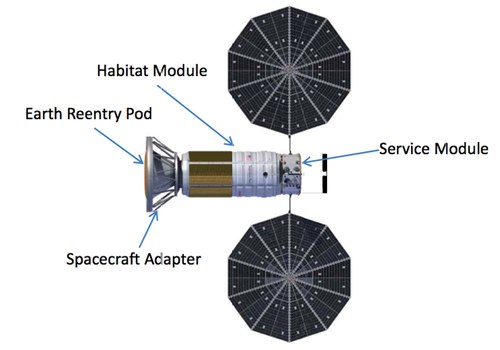

Illustration of the Inspiration Mars Vehicle Stack, the spacecraft that would take two people on a Mars flyby mission, as revealed by the organization in November. It makes use of a modified Cygnus spacecraft as the habitat module and a Orion spacecraft with enhanced heat shield to return the crew to Earth. (credit: Inspiration Mars) As noted yesterday, getting vehicles ready to carry people on brief suborbital flights has proven to take far longer than once thought, as companies struggled with technical and financial challenges. If suborbital commercial human spaceflight has been that difficult, the idea of private organizations sending people not just on suborbital or even orbital flights, but instead all the way to Mars, sounds like pure folly. Human Mars missions, after all, are the long-term (with emphasis on long) of NASA and other government space agencies. Yet, in 2013, two organizations took steps to do just that, although both face significant challenges in the year ahead.

In February, a new organization called the Inspiration Mars Foundation announced plans for human Mars flyby mission that, at the time, they believed could be privately funded. A two-person crew—ideally a husband and wife in late middle age—would launch in early 2018, fly past Mars later that year, and return to Earth 501 days after departure. The concept was the brainstorm of Dennis Tito, the multimillionaire best known for being the first space tourist to visit the ISS back in 2001, and he put together a team to flesh out the concept while providing additional funding.

At the time of the late February rollout of the plan, Tito said he expected to fund the mission privately, but that it would not explicitly be a commercial mission. Instead, Tito said he expected to raise most of the money philanthropically, although with perhaps the sale of sponsorships and media rights as well. Tito added that while Inspiration Mars would be open to selling some of the data collected during the mission to NASA, it was not otherwise seeking government funding to carry out the mission.

By November, though, Inspiration Mars’s plans had changed. The organization released a 60-day report on the mission concept that endorsed extensive use of NASA assets, in particular the Space Launch Systems (SLS) heavy-lift rocket and the Orion spacecraft. The architecture would require NASA to also accelerate development of a new upper stage for the SLS that, under even optimistic NASA plans, won’t be ready until the early 2020s.

That mission architecture would require a strong NASA role for the mission, and additional funding for the space agency. In testimony before the House Science Committee on November 20, the same day as the release of the 60-day report, Tito said he estimated Inspiration Mars needed $700 million in NASA funding to carry out the mission, not including the value of elements like the SLS (the mission makes use of the planned inaugural launch of the SLS, currently scheduled for late 2017 to send an uncrewed Orion spacecraft to the vicinity of the Moon and back.) The Inspiration Mars Foundation would raise a few hundred million dollars to cover the remaining costs of the mission: a far cry from what Tito said in February.

“We have just a couple of months to get some signals that would indicate serious interest developing,†Tito said in November, if Inspiration Mars was to remain on track for its planned end-of-2017 mission. However, his concept got a skeptical reaction from lawmakers at the hearing, and since then there’s been no sign of “serious interest” in the mission either in Congress or at the White House. There is, Tito said, a “backup” mission architecture that would not require launches until 2021: while 88 days longer, it would include flybys of Venus and Mars. Tito, though, warned that he expected other nations, in particular Russia and China, try to carry out such a mission if NASA didn’t support the earlier mission opportunity—although there’s been no signs of interest by officials in either country about it.

Mars One is planning a permanent human settlement on Mars within ten years, and used a unique astronaut selection process open to the public. (credit: Mars One/Bryan Versteeg) While Inspiration Mars seeks to send people on a flyby mission to Mars and back, another organization has even more audacious plans. Mars One wants to send people to the surface of Mars—to stay. The non-profit organization, based in the Netherlands, believes it can send a first crew of four people to Mars in the next decade and at a cost of just $6 billion. While the ability of Mars One to carry out that mission on that budget and schedule—as well as the ethics of sending people on one-way missions to Mars—has been questioned, the concept attracted a lot of interest in 2013.

Much of that interest centered around Mars One’s astronaut selection process. In April, Mars One started the process of accepting applications from any adult able to pay a registration fee ($5 to $73, an amount tied to the applicant’s per capita GDP), fill out an application form, and provide a brief video on why they should be selected. After the deadline for applications passed at the end of August, Mars One claimed it received “interest from 202,586 people from around the world.”

Most media outlets reporting on this interpreted that to mean that Mars One received over 200,000 completed applications, but analysis suggests the actual number may be far smaller. Back in May, when Mars One claimed it had already received 78,000 applications, this publication reported that the actual number was likely only a few percent of that, based on the number of applicant videos available on the Mars One website. That ratio appeared to hold up throughout the process, with fewer than 2,650 applicant videos available after the deadline passed.

Finally, just this past Monday, Mars One announced that 1,058 people had made it through the astronaut selection process and on to round 2. Those people—586 men and 472 women from 107 countries–will go through additional screening, including “rigorous simulations, many in team settings” to test applicants’ physical and emotional makeup, Mars One chief medical officer Norbert Kraft said in the press release. Mars One did not release additional details of the screening process, noting it is in “ongoing negotiations with media companies for the rights to televise the selection processes.”

Mars One also announced in December plans for a robotic precursor mission. That mission, slated for launch in 2018 (two years later than previously planned), will include a lander built by Lockheed Martin based on the design used for NASA’s Phoenix and InSight missions, as well as a communications orbiter built by Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd. Mars One has study contracts in place with the two companies, but was vague regarding how it would raise the several hundred million dollars needed to pay for the robotic mission—itself a small amount of the $6 billion it claims it needs for a human mission. Like Inspiration Mars, Mars One demonstrated in 2013 that going to the Red Planet requires a lot of green.

|

|

Recent Comments