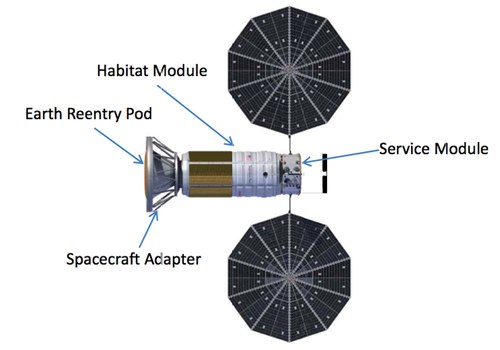

Illustration of the Inspiration Mars Vehicle Stack, the spacecraft that would take two people on a Mars flyby mission, as revealed by the organization in November. It makes use of a modified Cygnus spacecraft as the habitat module and a Orion spacecraft with enhanced heat shield to return the crew to Earth. (credit: Inspiration Mars)

As noted yesterday, getting vehicles ready to carry people on brief suborbital flights has proven to take far longer than once thought, as companies struggled with technical and financial challenges. If suborbital commercial human spaceflight has been that difficult, the idea of private organizations sending people not just on suborbital or even orbital flights, but instead all the way to Mars, sounds like pure folly. Human Mars missions, after all, are the long-term (with emphasis on long) of NASA and other government space agencies. Yet, in 2013, two organizations took steps to do just that, although both face significant challenges in the year ahead.

In February, a new organization called the Inspiration Mars Foundation announced plans for human Mars flyby mission that, at the time, they believed could be privately funded. A two-person crew—ideally a husband and wife in late middle age—would launch in early 2018, fly past Mars later that year, and return to Earth 501 days after departure. The concept was the brainstorm of Dennis Tito, the multimillionaire best known for being the first space tourist to visit the ISS back in 2001, and he put together a team to flesh out the concept while providing additional funding.

At the time of the late February rollout of the plan, Tito said he expected to fund the mission privately, but that it would not explicitly be a commercial mission. Instead, Tito said he expected to raise most of the money philanthropically, although with perhaps the sale of sponsorships and media rights as well. Tito added that while Inspiration Mars would be open to selling some of the data collected during the mission to NASA, it was not otherwise seeking government funding to carry out the mission.

By November, though, Inspiration Mars’s plans had changed. The organization released a 60-day report on the mission concept that endorsed extensive use of NASA assets, in particular the Space Launch Systems (SLS) heavy-lift rocket and the Orion spacecraft. The architecture would require NASA to also accelerate development of a new upper stage for the SLS that, under even optimistic NASA plans, won’t be ready until the early 2020s.

That mission architecture would require a strong NASA role for the mission, and additional funding for the space agency. In testimony before the House Science Committee on November 20, the same day as the release of the 60-day report, Tito said he estimated Inspiration Mars needed $700 million in NASA funding to carry out the mission, not including the value of elements like the SLS (the mission makes use of the planned inaugural launch of the SLS, currently scheduled for late 2017 to send an uncrewed Orion spacecraft to the vicinity of the Moon and back.) The Inspiration Mars Foundation would raise a few hundred million dollars to cover the remaining costs of the mission: a far cry from what Tito said in February.

“We have just a couple of months to get some signals that would indicate serious interest developing,†Tito said in November, if Inspiration Mars was to remain on track for its planned end-of-2017 mission. However, his concept got a skeptical reaction from lawmakers at the hearing, and since then there’s been no sign of “serious interest” in the mission either in Congress or at the White House. There is, Tito said, a “backup” mission architecture that would not require launches until 2021: while 88 days longer, it would include flybys of Venus and Mars. Tito, though, warned that he expected other nations, in particular Russia and China, try to carry out such a mission if NASA didn’t support the earlier mission opportunity—although there’s been no signs of interest by officials in either country about it.

Mars One is planning a permanent human settlement on Mars within ten years, and used a unique astronaut selection process open to the public. (credit: Mars One/Bryan Versteeg)

While Inspiration Mars seeks to send people on a flyby mission to Mars and back, another organization has even more audacious plans. Mars One wants to send people to the surface of Mars—to stay. The non-profit organization, based in the Netherlands, believes it can send a first crew of four people to Mars in the next decade and at a cost of just $6 billion. While the ability of Mars One to carry out that mission on that budget and schedule—as well as the ethics of sending people on one-way missions to Mars—has been questioned, the concept attracted a lot of interest in 2013.

Much of that interest centered around Mars One’s astronaut selection process. In April, Mars One started the process of accepting applications from any adult able to pay a registration fee ($5 to $73, an amount tied to the applicant’s per capita GDP), fill out an application form, and provide a brief video on why they should be selected. After the deadline for applications passed at the end of August, Mars One claimed it received “interest from 202,586 people from around the world.”

Most media outlets reporting on this interpreted that to mean that Mars One received over 200,000 completed applications, but analysis suggests the actual number may be far smaller. Back in May, when Mars One claimed it had already received 78,000 applications, this publication reported that the actual number was likely only a few percent of that, based on the number of applicant videos available on the Mars One website. That ratio appeared to hold up throughout the process, with fewer than 2,650 applicant videos available after the deadline passed.

Finally, just this past Monday, Mars One announced that 1,058 people had made it through the astronaut selection process and on to round 2. Those people—586 men and 472 women from 107 countries–will go through additional screening, including “rigorous simulations, many in team settings” to test applicants’ physical and emotional makeup, Mars One chief medical officer Norbert Kraft said in the press release. Mars One did not release additional details of the screening process, noting it is in “ongoing negotiations with media companies for the rights to televise the selection processes.”

Mars One also announced in December plans for a robotic precursor mission. That mission, slated for launch in 2018 (two years later than previously planned), will include a lander built by Lockheed Martin based on the design used for NASA’s Phoenix and InSight missions, as well as a communications orbiter built by Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd. Mars One has study contracts in place with the two companies, but was vague regarding how it would raise the several hundred million dollars needed to pay for the robotic mission—itself a small amount of the $6 billion it claims it needs for a human mission. Like Inspiration Mars, Mars One demonstrated in 2013 that going to the Red Planet requires a lot of green.

Leave a Reply